"Poetic Science," which runs from 12 October 2007 through 10 February 2008, is the first area solo show of works by book artist and binder

Daniel Kelm, who with his wife and fellow artist, Greta Sibley, runs the

Garage Annex School for Book Arts in Easthampton.

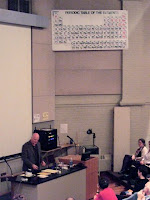

Kelm's opening lecture to a standing-room only crowd in Stoddard Hall was in effect an intellectual and aesthetic autobiography. He recounted his itinerary from budding juvenile inventor, to student and teacher of chemistry, to book artist. What was most striking, in addition to the sheer enthusiasm for the subject, was the sense of logical consistency: At the end, one came away with the impression that the present destination was inevitable, at least to the extent that all the elements of his wide-ranging intellect and equally probing art fitted seamlessly together, and that each would seem incomplete without the others.

In a sense, it was a romance: Kelm fell in love with chemistry at age 7. He related how, from an early age, he was drawn to science not only as technical knowledge, but also as the wondrous (and to a child, quasi-magical) means of exploration and transformation of the materials around us. He described the curiosity triggered by his father’s work as a photographer and related some of his own early scientific misadventures, such as an attempt to make “perfume,” which instead yielded mainly a cloud of toxic chlorine gas that cleared the house and led to his “laboratory” being banished from the family basement. He retains both a sense of the magic and the passion for experimentation.

Kelm explained how science led him to books, which eventually directed him more deeply into science, which in turn ultimately led him back to books. After presenting spreads from the how-to experiment handbooks that so fascinated the boys of the baby boom generation, he described falling in love with books as objects as well as vessels of knowledge (noting in passing that Daniel Faraday was also a bookbinder). He was drawn in particular to the tactile elements in the tooled covers of old books, a revelation that will instantly make sense to anyone familiar with Kelm’s own highly sculptural creations, which push our notions of book structures to their limit.

As a student and teacher of chemistry, Kelm was equally drawn to philosophy. In place of what he called the Baconian belligerency of modern science, which viewed nature as an opponent to be conquered and despoiled, he welcomed the notion of interdependency and gentle mystery that he found in alchemy. Science, he lamented, had become soulless. In many ways, his views echo the plaints of

diverse early nineteenth-century thinkers, from Blake to Goethe to Mary Shelley (it is no coincidence that a number of the German Romantics, such as Novalis, were trained in metallurgy and mine engineering).

Kelm devoted a good deal of the lecture to the description of his own alchemical work, in particular, attempts to build ever more efficient refining furnaces, which he evocatively described as performance sculptures (one can be seen in the

exhibition). Moderns, he said, stress the spiritual side of alchemy, whereas he wanted to redirect attention to its physical aspects: Even though our scientific theories may now be different, the alchemists made great strides in technical ability. He nonetheless also took pains to explain why he found the mythical or allegorical side of alchemy so compelling as a path to a renewed sense of wonder at the processes of nature--for example, the recovery of gold from the heating of metal ash wrapped in lead as the emblematic encounter of the "gray wolf" and "rejuvenated king."

Kelm’s most explicit engagement with alchemy as subject rather than principle of his art occurs in the “Templum Elementorum,” commissioned as part of a Smithsonian exhibition on

“Science and the Artist’s Book” (1995).

Exhibitors were required to base their work on a text held in the Dibner Library’s collection, and Kelm chose Vannoccio Biringuccio’s sixteenth-century

De la pirotechnia (On working with fire), for its description of an innovative tower-like furnace:

Inspired by this motif, Kelm created four columnar glass vessels, keyed to the four elements and marked by their associated colors: red for Fire; yellow for Air; white for Water; and black for Earth. Each container holds a book which represents the “voice” of that element and includes alchemical symbols and words that relate to some relevant aspect of the project. These books also include examples of the related elemental metals: lead for Earth, copper for Water, tin for Air, and iron for Fire. He called the book Templum Elementorum, which means “sanctuary of the elements” in Latin.

view videoAlthough those of a strictly scientific and rational nature may raise an eyebrow at Kelm’s statement that objects have consciousness, few of us would deny that material objects, and above all, works of art, can speak to us by engaging our senses as well as our intellects, often in inexplicably powerful ways. Certainly, this is the belief that one takes away from the stunning exhibit, as I hope further postings on this blog will affirm.

Dan Kelm doing chemistry and displaying "Templum Elementorum" while teaching "Alchemy and the Artist's Book" at Hampshire College, Fall 2002.